Hospital Price Discrimination Is Deepening Racial Health Inequity

This article originally appeared in NEJM Catalyst, co-authored with Alan Kaplan, MD.

Hospital Price Discrimination Is Deepening Racial Health Inequity

As hospitals seek to increase revenues by attracting more privately insured patients (who are disproportionately white), a complex pricing dynamic tends to channel both private and public funding away from hospitals with more Medicaid patients (who tend to be disproportionately non-white). Policymakers can interrupt the cycle of price discrimination and hospital-driven segregation through a range of interventions to narrow the price divergence across coverage markets.

Summary

Covid-19 has shed harsh light on America’s deep health inequities, and mounting evidence points to the health care system’s underlying economics as a key cause. As hospitals exert pricing power in the private insurance market, their pricing strategy re-directs financial resources to facilities serving Americans with private coverage, a group which is disproportionately white. Those resources pay for staff, facility upgrades and acquisitions to capture more private patients and further augment leverage. This cycle of price discrimination segregates local markets, funneling Medicaid patients – who are disproportionately Black and Hispanic – to hospitals with fewer resources and inferior clinical quality. Policymakers have a range of options to interrupt this cycle, including tools which borrow from existing regulations that govern price negotiations in the Medicare Advantage market. Such interventions – some of which appear in President-elect Biden’s healthcare plan – could mitigate acute inequities in American healthcare, while also boosting the affordability of private health coverage.

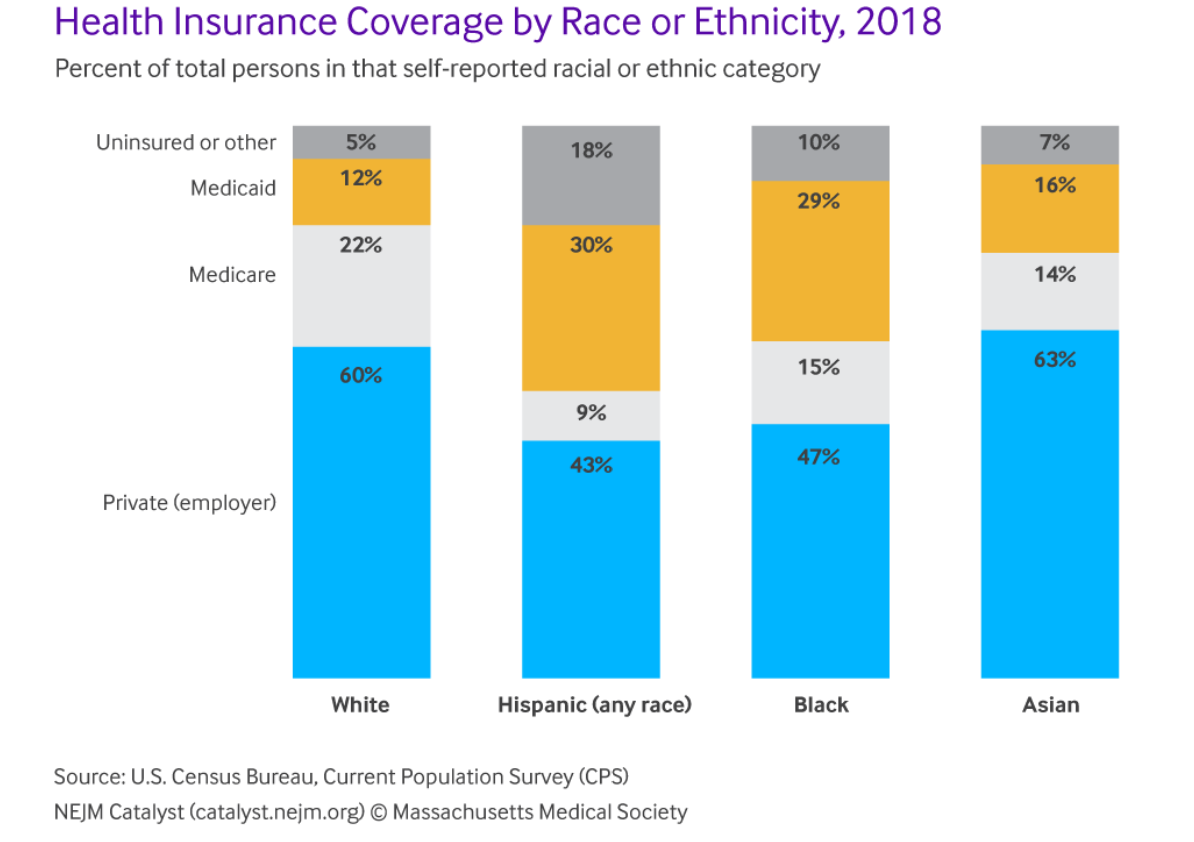

Price discrimination’s role in health inequity is rooted in the racial and ethnic makeup of enrollees in different coverage programs, policy-driven variations in pricing among those programs, and the mechanics of subsidized health insurance. In 2018, more than 80% of white Americans were covered by an employer or Medicare, as compared with only 62% of Black Americans and 52% of Hispanic Americans. Black and Hispanic Americans are roughly two and a half times as likely to rely on Medicaid coverage. (See Figure 1)

In and of themselves, racial or ethnic enrollment variations across coverage schemes need not exacerbate health inequity. Indeed, Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act narrowed racial disparities in the uninsured rate and access to care.1 And quality measures of primary and preventive care (e.g. seasonal flu shots, blood pressure checkups and colon cancer screening) are similar across health plans, whether privately or publicly funded.2 However, as we describe below, increasingly divergent pricing between publicly and privately funded plans creates strong incentives for hospitals to lure patients with private (primarily employer-sponsored) insurance plans, while funneling ever more financial resources (both private and public) to this wealthier and whiter population.

Diverging prices depending on type of coverage

Spiraling hospital prices for the privately insured are well-documented. While private health plans paid only 110% of Medicare rates in the late 1990s, average private prices for inpatient care surpassed 200% of Medicare by 2017.3 For outpatient hospital care, private plans pay nearly 300% of Medicare rates. These price levels are extreme by any measure, and so very financially attractive. MedPAC has estimated that Medicare’s hospital rates are 50% higher than hospital prices in other advanced economies4; this implies that an American hospital treating a privately-insured inpatient often enjoys prices which are three to four times the price for a similar service at a European hospital.

Meanwhile, though overall average Medicaid payments for hospital care are largely comparable to Medicare, differences in the payment structure can make a given Medicaid enrollee the least profitable patient in a hospital. Medicaid’s hospital payments include base rates for certain diagnosis-related groups – paid on a fee-for-service basis – and various supplemental and disproportionate share payments. Combined, these payments reach 106% of Medicare rates, as a nationwide average, but the base fees average only 78% of Medicare prices.5 Since the supplemental payments are usually allocated on a lump sum basis, a given Medicaid patient yields significantly less revenue than an individual with Medicare or commercial insurance.

For example, in 2017 the average hospital was paid approximately $10,700 for treating a Medicare patient with heart failure and shock (MS-DRG-291).6 Per separate analyses by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission and the RAND Corporation, that payment would have dropped to roughly $7,500 if the patient were covered by Medicaid (base rate only), but would have averaged approximately $21,000 if the patient were privately-insured [these estimates apply the 70% Medicaid base rate-to-Medicare ratio estimated for MS-DRG-291 in the MACPAC study cited above, and the 204% private insurance-to-Medicare ratio calculated (for inpatient prices) in the RAND Corporation study above]. Given that Medicare prices exceed the variable cost of inpatient care by about 8%, such high private prices imply a profit margin above 50%.7 This considerable profit potential creates a powerful incentive for hospitals to focus their outreach and services on the privately insured.

Your tax dollars at work

Hospitals have multiple levers to boost prices for the privately insured, which are fairly well-documented. Mergers within and across local markets and hospital acquisitions of physician practices (horizontal and vertical consolidation, respectively) play substantial and growing roles. Many metro area hospital markets are now “highly concentrated” (i.e. not competitive).

Hospitals also exercise significant pricing power through information asymmetries. For many conditions, patients (and their primary care physicians) have little information that would allow them to make an informed choice among facilities for scheduled care, or to select or decline specific tests or interventions, particularly when ill or under duress, or even to choose a different facility in an emergent situation. All of these factors tend to increase hospitals’ pricing power, absent offsetting regulations or other constraints. In general, such constraints exist in the Medicare and Medicaid segments, but not for employer-sponsored or individual private plans.

Because all private health plans receive federal subsidies, either directly or via tax deductions, when hospitals exercise this pricing power, they also tilt taxpayer expenditures on hospital care toward facilities that treat privately insured patients. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that federal subsidies accounted for roughly 25% of the dollars flowing through private health plans in 2019, which included nearly $500 billion destined for hospitals.12 Federal subsidies for hospital services for the privately insured are comparable to total federal spending on hospital care through Medicaid and will soon exceed them if current trends continue. Over time, private plan subsidies and escalating hospital prices for private patients13 will steadily channel more federal health care dollars toward higher-income, disproportionately white patients. By 2026, the CBO expects federal subsidies for employer plans alone to exceed all federal spending on Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

While the correlation between a hospital’s prices and objective measures of clinical quality is fairly weak,15 there is evidence that hospitals with higher margins receive higher marks from patients on the subjective experience of care. And hospitals appear to make investments in patient satisfaction and clinical quality (e.g., through technology or processes of care) in a bid to attract higher-margin private patients.16 However, as hospitals use cash flow from private health plans to gain market share (through marketing or acquisitions) or enhance quality, they also accumulate more pricing power, which then heightens the financial incentive to tilt services even further toward the privately insured. As explained above, those high prices draw in more federally subsidized health dollars, converting them into new buildings, services and technology geared primarily to the privately insured. Over time, this cycle shifts public and private resources to hospitals that serve a disproportionately white population because of the racial skew of private insurance mentioned above. The result is that white populations have better access to higher quality facilities than Black and Hispanic populations do.

Separate and unequal

Nationally, Himmelstein et al. identified clear evidence of this imbalance in resources, noting that “hospitals that serve people of color are substantially poorer in assets than other hospitals,” and are less likely to offer a range of capital-intensive services.17 Likewise, the site of care is a major factor in racial disparities in clinical outcomes.18 Here, we examine evidence that price discrimination fuels a cycle in which hospitals pursue higher-margin privately insured patients. This cycle contributes to racial inequities in care by channeling Medicaid patients to facilities with fewer resources and often lower clinical quality.

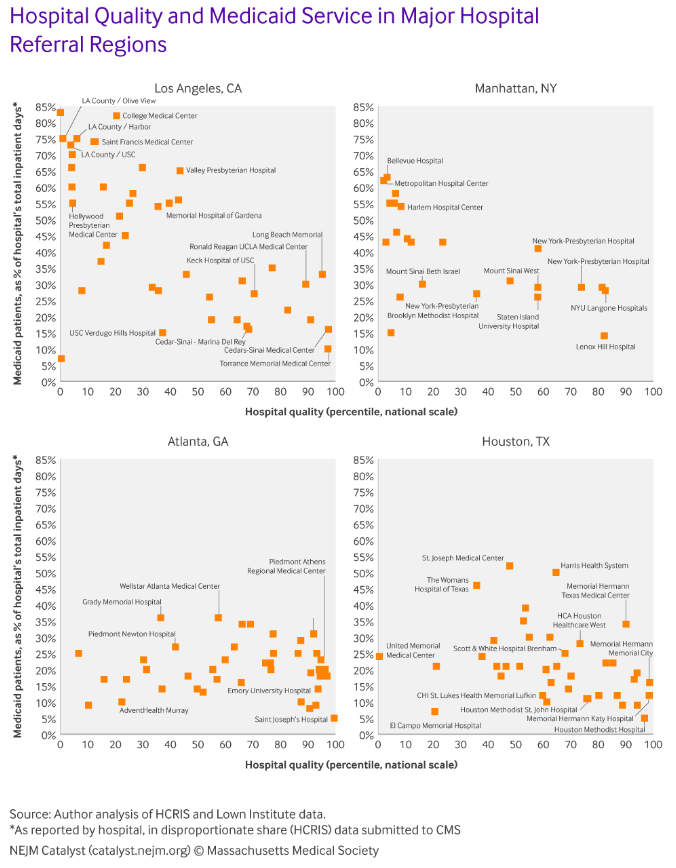

Figure 2 draws on data from hospital cost reports and clinical quality measures collected by the Lown Institute to illustrate unequal facility usage by Medicaid patients in four of the country’s largest hospital referral regions.19 In Los Angeles, hospitals with clinical quality above the national median allocate just 23% of inpatient days to individuals with Medicaid, as compared with 54% of inpatient days for hospitals in the bottom two quality quartiles. Similar disparities emerge in New York and Houston, albeit to a lesser degree. In all these markets, many facilities with the highest objective quality scores serve very few Medicaid patients, who instead rely on publicly run facilities and small private hospitals with relatively poor clinical quality. The distribution appears less uneven in Atlanta, though some high profile (and high quality) medical centers, such as Emory University Hospital, serve Medicaid patients at levels far below the local average.

Figure 2 draws on data from hospital cost reports and clinical quality measures collected by the Lown Institute to illustrate unequal facility usage by Medicaid patients in four of the country’s largest hospital referral regions.19 In Los Angeles, hospitals with clinical quality above the national median allocate just 23% of inpatient days to individuals with Medicaid, as compared with 54% of inpatient days for hospitals in the bottom two quality quartiles. Similar disparities emerge in New York and Houston, albeit to a lesser degree. In all these markets, many facilities with the highest objective quality scores serve very few Medicaid patients, who instead rely on publicly run facilities and small private hospitals with relatively poor clinical quality. The distribution appears less uneven in Atlanta, though some high profile (and high quality) medical centers, such as Emory University Hospital, serve Medicaid patients at levels far below the local average.

This pattern, which appears across the majority of the hospital referral regions in our sample (>2,500 hospitals across ~300 HRRs) comports with other work showing hospitals with advanced critical care capabilities are more likely to transfer Medicaid patients than privately insured patients.20 It is also consistent with known racial disparities in the treatment and outcomes for a variety of complex clinical conditions such as acute myocardial infarction and organ transplantation.

Black and Hispanic Americans are three times more likely to contract Covid-19 and twice as likely to die from the disease.23 In some predominantly Black counties, the mortality rate is nearly six times higher than predominantly white counties.24

A solvable systemic problem

As we argue here, racial and ethnic health disparities are inextricably linked to the price discrimination embedded in America’s hospital industry. For financial reasons, many hospitals focus on serving a disproportionately white population with taxpayer-subsidized private health plans. A lack of regulation allows those hospitals to exercise market power and achieve unusually high profit margins within this population. This funnels public and private resources to hospitals not equally accessible to many Black and Hispanic patients who rely more heavily on Medicaid coverage. Rising private prices, relative to public plans, heighten incentives for hospitals to discriminate by payer, and so steadily deepen health inequities.

Policymakers can interrupt the cycle of price discrimination and hospital-driven segregation through a range of interventions to narrow the price divergence across coverage markets. In some states, there may be a case for modest increases in Medicaid rates, but it is entirely unrealistic (and unwise) for states to double or triple Medicaid payments to hospitals, so most of the adjustment must come through lower prices under employer-sponsored and individual private plans.

In a thorough recent analysis, Matthew Fiedler examines four pathways to lower provider prices in the privately-insured market.25 Several of these build on tools already used in the Medicare market, where many of the same hospitals and insurers bargain over prices for patients with privately-run Medicare Advantage plans, but reach very different numbers from those imposed on patients with employer-sponsored plans.

First, regulations could limit out-of-network prices, a constraint on provider pricing power which is likely to lower in-network prices for some services (e.g., emergency care), but may be ineffective when a hospital can simply refuse to treat patients with a given health plan unless prices remain at today’s nosebleed levels.

Second, policymakers could simply place a cap on all hospital prices, whether care is delivered in or out-of-network. This would likely place firmer downward pressure on prices, but hospitals could then exert their market power in other ways, such as by refusing to participate in quality or patient safety programs, or by re-classifying some services (e.g. inpatient food service) to evade the cap.

Third, regulators could institute a “default contract” specifying prices, patient access and service levels – which applies to all hospitals and insurers that have not otherwise negotiated a private agreement. This would address many of the evasion and market power issues, while still allowing private plans and hospitals to voluntarily agree on premium prices for differentiated clinical outcomes or patient satisfaction, and to experiment with value-based payment models, just as occurs in Medicare Advantage and Managed Medicaid.

Finally, a public option – like that proposed in President-elect Biden’s healthcare plan – could lower hospital prices in private plans, if the public option paid regulated rates, if providers were required to accept patients with the new public plan, and if the public option is available to most or all patients who currently rely on the employer and individual coverage markets.

In addition to the steps above, policymakers could take narrower, piecemeal steps to limit hospital prices for certain services, and to curb or reverse provider consolidation. Such limits might dampen or slow price inflation in the privately-insured segment. However, relying solely on antitrust enforcement is unlikely to reverse (and may not even arrest) a multi-decade, nationwide pattern of diverging prices and the resulting inequities in patient access and clinical quality.

The high cost of American healthcare has been a perennial political topic, and attention is increasingly (and rightly) focused on the primary root cause – the underlying prices for healthcare services and products. Often, this debate centers on the economic hardships of employers (who must absorb these ever-higher prices), or patients (who must either pay more out of pocket or forgo care). However, as we have argued here, hospital price discrimination also contributes to the deep-seated health inequities that Covid-19 has shown in stark relief. Curbing hospital prices, then, is not simply about the affordability of private health coverage, but an imperative in any effort to ensure equitable access to high-quality care, regardless of race or ethnicity.

Footnotes and citations available via NEJM Catalyst, without a paywall.