States are debating sweeping health reform. Time for a plan.

In many states, the fall elections will feature debates over the perils and promise of “single payer” health coverage. Gavin Newsom, California’s likely next governor, has offered vocal but vague support, while his Republican opponent demurs, plumping (equally vaguely) for “more competition.” New York’s Assembly has approved a reform bill tagged with the “single payer” label, Washington state is likely to see new legislation later this year, and a gubernatorial candidate in Michigan has proposed a state-run scheme to cover all residents.

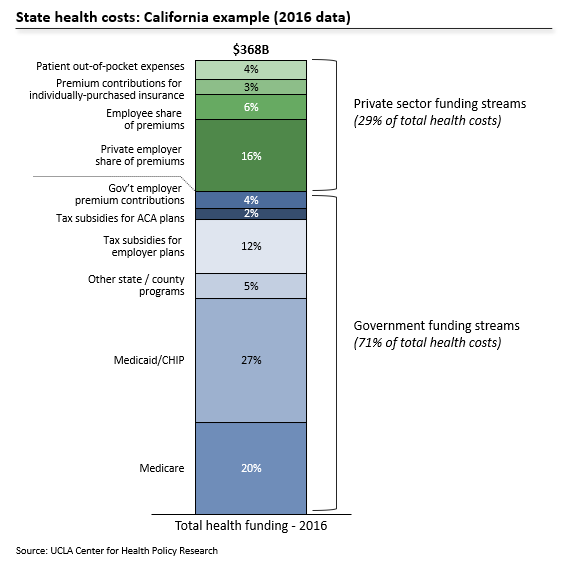

“Single payer” is misleading shorthand, but simpler, universal health insurance may attract voters fed up with uncertainty and eyewatering bills, and it could free businesses from managing an expensive, complicated benefit. Yet, as we’ve all now learned, healthcare is “unbelievably complex,” and the system’s vast complexity and sheer cost could easily frustrate state-led reform. In California, for example, abrupt change would re-route hundreds of billions of dollars across the world’s 5th-largest healthcare market, which risks disrupting care and squeezing the state’s 1.4 million health workers. How can reformers navigate these shoals, while setting their states on a path to affordable, universal coverage?

Three broad principles would help. First, tackle costs before coverage. Second, exclude those already eligible for Medicare, which is popular, efficient, and well-funded through the Federal purse. Finally, build on Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces to underpin a phased transition to the new statewide program.

Addressing costs before coverage will deliver quicker savings to more voters and businesses, while curbing the eventual burden on state budgets. Today, only 5 – 10% of Californians, New Yorkers and Michiganders lack insurance, but huge majorities worry about health bills. Curbing costs in the near-term can also blunt fear of swingeing tax hikes, and distinguish state reform from the ACA, which prioritized coverage but did less to check continued health inflation. A reform roadmap could start with a statewide mechanism to rationalize pricing, akin to the model in Germany, which enjoys universal coverage, lower costs and an active private insurance market with >40 competitors. In California, Ash Kalra’s bill (AB 3087) outlines one possible framework; the legislation would create a nine-member commission to set standard hospital and physician fee schedules, using Medicare rates as a floor. This approach would bring sanity and predictability to health charges, in a state where a routine appendectomy can cost anywhere from $1,500 to $182,000. And, because the program eliminates variation across private plans, and adopts Medicare’s underlying payment methodology, it will chip away at wasteful administrative overhead for hospitals and physicians.

Meanwhile, the new state coverage schemes should focus only on non-Medicare patients, as in the Michigan proposal. Medicare beneficiaries rate their coverage highly, nearly all physicians and hospitals accept Medicare reimbursement, and the federal plan is efficient, with administrative costs per member roughly one-third the level seen in private insurers. There is little reason for states to replace a program that is working fairly well. Moreover, excluding Medicare trims the financial scope of a new program (by ~20%, in most states) and avoids the Federal waivers and administrative mechanics which would be required to re-route Medicare funds through a new local intermediary.

Last, to build an on-ramp for consistent, universal coverage, states could merge Medicaid and ACA enrollees into a single patient pool, with competing private plans and a sliding scale of premium subsidies. Overall funding will not change – subsidies would match current levels, based on multiples of the federal poverty level. A unified pool will eliminate coverage gaps when income thresholds bump a patient from one program to another, which disrupts preventative care. It will also create a larger, more competitive market for private insurers, many of whom already offer (separate) Medicaid and ACA plans. Critically, the new pool would force state agencies to streamline bureaucracy which could otherwise dent popular support, if extended to more middle-class voters. In California, for example, Medicaid enrollment is currently a multi-month process, involving county review, 45 days of coverage under the state’s fee-for-service scheme, and then assignment to a privately-managed plan. Once the kinks are ironed out, states can nudge residents into this pool through presumptive, automatic enrollment, and by replacing tax exemptions for employer plans with tax-advantaged vouchers to purchase insurance through the new, consolidated marketplaces. With the right regulatory framework, these larger marketplaces can also simplify coverage parameters (e.g. copays) and payment rules, eliminating some of the confusion which forces doctors and hospitals to spend heavily on staff and technology, just to understand what services are covered by a given patient’s plan. States will also retain the option to offer residents a pure public plan (i.e. without a private insurance intermediary) through these marketplaces, much as the elderly can choose either traditional Medicare or a privately-administered “Medicare Advantage” plan.

This sort of phased approach would build credibility for a state-led program, while curbing runaway health costs in the interim. Done well, it could ensure universal coverage, eliminate many administrative hassles for doctors, and attract entrepreneurs who want to build their businesses, not manage health benefits. Without a prudent roadmap, however, states risk a damaging crackup, which could undermine reform efforts elsewhere.